Today is the 35th anniversary of my brother Ben’s death. On most years, my wife and I mark the day by taking my mother Elisabeth, who just celebrated her 94th birthday, to a park next to Ben’s old middle school. We sit on a bench that my sister Miriam installed in his memory and gaze up at a linden tree that friends planted for him, musing about how tall the tree has grown and how much time has passed.

As “big” anniversaries approach, fearing that Ben’s memory will fade and lessons of his life will be lost, I look for ways to share his story and news of the project that he helped launch in Nicaragua. This year, as in the past, I began by contacting Rebecca Leaf, the engineer who carried on Ben’s work and has been a leader of ATDER-BL (Association of Rural Development Workers—Benjamin Linder) since it was founded. Her update inspired me and may inspire you, regardless of our varied views about the political situation in Nicaragua.

The most encouraging news is that the rural development project that Ben helped launch 37 years ago continues moving forward and remains true to its original goals despite contra murders, hurricanes, near bankruptcy, shifting politics, and immense technical challenges.

Having watched many well-meaning initiatives come and go, I asked myself why this one has succeeded, and I believe there are three reasons. First, the original goal–building small hydroelectric and potable water systems, with community members doing most of the work and gaining critical skills in the process–was realistic and supported by the communities involved. Second, the key individuals have been models of integrity, teamwork, respect, resourcefulness, and perseverance. Finally, people like yourselves, as well as international aid organizations, have provided support.

When Ben was killed, the very small plant that he helped build in El Cuá provided electricity to several hundred homes. Today, approximately 55,000 people receive electricity from two plants built by ATDER-BL, one in San José de Bocay, where Ben was killed, and the other in El Bote. The two hydro systems are reliable, the streams and rivers that power them are renewable, and they pay for themselves with affordable rates.

Electricity has rapidly transformed communities, including bringing major improvements in education and health care. Schools that taught only first through third grade can now teach all grades because teachers from larger towns are willing to work where there is electricity. “Similarly, when villages with electricity become more attractive to qualified nurses or medical staff, a half-abandoned health post can become an effective small health center that provides reliable basic daily medical attention to the local community,” writes Rebecca. I encourage you to read more in this excellent report that she wrote with José Luís Olivas, a leader of APRODELBO (Association for Electrical Development, Bocay), an organization of long-time Bocay residents that owns and operates the plant and the electrical grid it serves.

When I scrolled through the photos that Rebecca sent, I was struck by how much hard physical labor many hundreds of people have put into building their own electric and potable water systems. Sandinistas and Liberals, Catholics and Evangelicals sweated together to meet their common needs.

Through this work, dozens of workers have been trained as electricians, linesmen, mechanics, welders, and surveyors as they built, operated, and maintained the projects. Many still work for ATDER-BL, which has a staff of 31, or for APRODELBO; others have started their own businesses, contributing to the development of the region.

Farm families in the watersheds of the hydro plants have enthusiastically adapted their practices to prevent erosion. ATDER-BL initiated watershed protection to prevent soil from rapidly filling up the reservoirs behind the dams it had built. It viewed farmers as allies and helped them improve crop production while limiting erosion. By providing training, ATDER-BL has made it possible for farmers to increase their incomes and remain on their lands rather than cutting and burning down more forest as their lands lose fertility. This presentation explains the process of trial and error that led to effective watershed protection.

All of this work has been done by and for the people, without being driven or distorted by the drive for profit. Both ATDER-BL and APRODELBO are nonprofits, and their entire staff is paid reasonable but modest wages, allowing them to provide electricity, drinking water, and welding and machinist work at affordable prices.

As I watch in dismay as the world is consumed by war and climate change, both of them driven by the insane lust for wealth and power, I take some encouragement from the glimpse of an alternative provided by this work in Nicaragua. Not every region is suitable for hydropower, but if the people of a very poor region in a very poor country can improve their lives without fossil fuels, we all can.

With hope and gratitude,

John Linder

P.S. – Whenever I write letters like this, I feel an uneasy sense of what I recently read is called “imposter syndrome,” knowing that many people contributed much more than I have to this work, including risking their lives, and know about it firsthand rather than by email. I would like to thank all of those people, some of whom may be reading this letter.

I would also like to thank Green Empowerment, which was founded by Michael and Francie Royce, neighbors and friends of my parents, and has supported the work of ATDER-BL and hundreds of similar efforts throughout the world.

This didn’t begin as a fundraising letter, but if you would like to help, there is a need. ATDER-BL recently located a site on the Santa Teresa River that could power a 1,500 kilowatt hydro system. Contributions to Green Empowerment made in Ben’s memory continue to support energy and water projects in Nicaragua and will support preliminary studies, designs, and permits. Contributions to Green Empowerment made in Ben’s memory will support preliminary studies and technical designs.

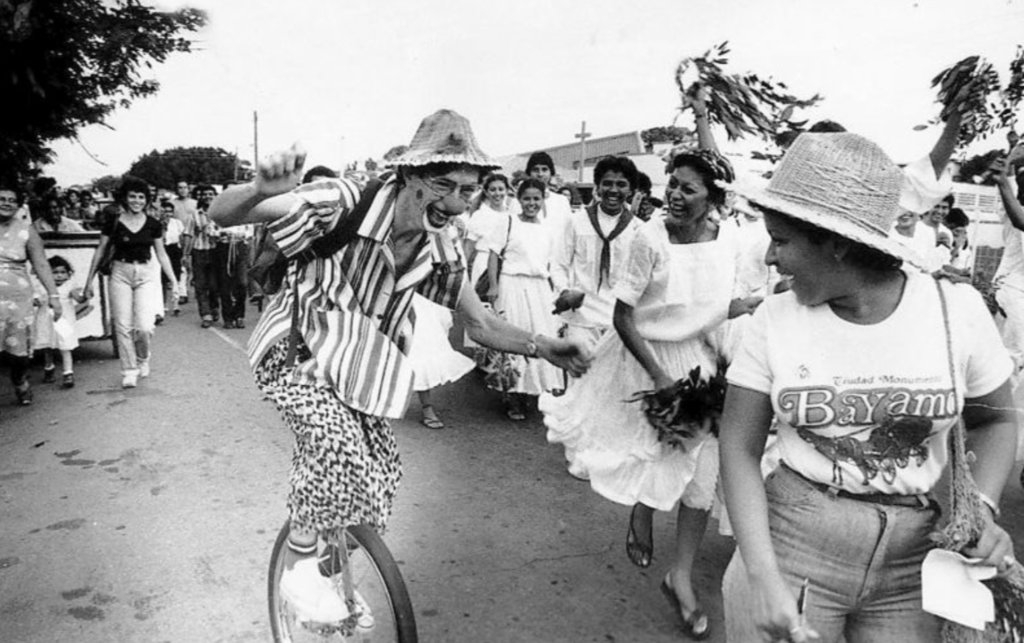

Every year, the teachers and students of San José de Bocay, and many other townspeople, hold a celebration to remember Ben and his coworkers Pablo Rosales and Sergio Hernandez, who were also killed in the contra attack.

During the 2020-2021 school year, a Canadian organization paid teachers to provide extra classes every day for students in two schools in the Los Angeles watershed in Bocay. I was impressed to learn that not only those students who had missed school, but nearly all of the schools’ 130 students participated in the program. Parents were very appreciative, and students made significant gains. Parents were especially supportive of hands-on classes conducted by ATDER-BL’s agronomist where both they and their children learned to grow vegetables in raised beds to mitigate the many diseases that make it very difficult to grow vegetables in the region’s soggy soil.

APRODELBO and ATDER-BL build approximately one potable water system each year for rural communities with funds donated from the United States, Spain, and Japan. Community members contribute a large amount of volunteer labor and manage the completed projects. ATDER-BL uses extra income from electricity sales to extend its grid to rural communities. In recent years, the government carried out a program of rural electrification and built 15 grid extensions in the Cuá-Bocay region. ATDER-BL takes on the operation and long-term maintenance costs of these new lines.ATDER-BL has installed more than 20 micro-turbines serving small remote villages. All of the turbines are built in ATDER’s machine shop. Villagers do most of the labor, receive training as plant operators, and form committees to operate the electric service.

Ben’s Legacy and Green Empowerment

Green Empowerment was founded at a crossroads of individuals, ideals, and Ben’s legacy. Ben’s family started the Ben Linder Memorial Fund to continue to support Ben’s work and ran it for 10 years. In 1997, the Royce family joined with the Ben Linder Memorial Fund to bring renewable energy solutions to social justice issues around the globe. Ben’s father was a founding Board member of Green Empowerment. The organization continues to support the work of Ben’s colleagues and friends and carries his vision for a more equitable world forward through authentic partnerships across the globe.

Read more about this connection in Francie Royce’s blog post 5 years ago honoring the 30th anniversary of Ben’s murder and reflecting on the moment she heard the news.

Donations made to Green Empowerment in Ben’s memory continue to support renewable energy and clean water projects in Nicaragua. Donate Here!

Dear John, Thank you for sharing Ben’s memory and his legacy.

Although , I never met him in person , his spirit leaves on in my heart. I learned about Ben after joining the Ben Linder brigade, a group of Portland locals involved in community work and social justice. I learned about Ben’s efforts, altruism and his ultimate sacrifice. I met his father, and other members of his family and I was inspired and committed to continue his work. As a Ben Linder brigade member, I traveled to Nicaragua in 1989 to help the community of Corinto together with a group of ~10 committed volunteers.

As a physician, I surveyed the medical records of the local hospital to understand the epidemiology of childhood morbidity and mortality and to gather information on the health needs of the pediatric population, the hospital and the community of Corinto. In the process, we engaged the community, the local medical team, and community leaders.

My team members contributed with their skills to make critical hospital building improvements that contributed to better clinical services to community patients.

Hope to continue being involved in Ben’s legacy and community service.